A referendum set to appear on the May 20 ballot asks whether Pittsburgh should make a rule that keeps its water and sewer system — currently owned by the city — from being sold to private companies. Here is the exact wording of the question:

“Shall the Pittsburgh Home Rule Charter be amended and supplemented by adding a new Article 11: RIGHT TO PUBLIC OWNERSHIP OF POTABLE WATER SYSTEMS, WASTEWATER SYSTEM, AND STORM SEWER SYSTEMS, which restricts the lease and/or sale of the city’s water and sewer system to private entities?”

Voting “yes” means you agree Pittsburgh should add this rule to the Pittsburgh Home Rule Charter. You can read the full text of the proposed Home Rule Charter Amendment by visiting tinyurl.com/water-ballot-measure-pgh-2025.

A transfer 30 years in the making

This question is important now because as of Sept. 1, Pittsburgh Water (formerly Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority or PWSA) will have the right to buy the water system from the City of Pittsburgh for $1. This was part of a 1995 agreement between the city and Pittsburgh Water that essentially created the utility company. In exchange, Pittsburgh Water agreed to pay almost $100 million in rent for its water pipes, sewer pipes and other infrastructure.

If the referendum does not pass, Pittsburgh Water will be able to sell the water system once ownership transfers from the city to the utility company. Pittsburgh Water’s current board of directors says it is committed to staying public and supportive of the referendum. But without the new rule, nothing would prevent a future board with different members from deciding to sell.

A Pennsylvania law, Act 12, has made water systems across the state more attractive to private companies since it passed in 2016. Act 12 was supposed to encourage investors to take over struggling public water systems when cities and towns lack funds to maintain them. It did so by allowing companies to pass on the costs of buying and maintaining water systems to their customers — whose water bills skyrocket.

Fighting to keep water public

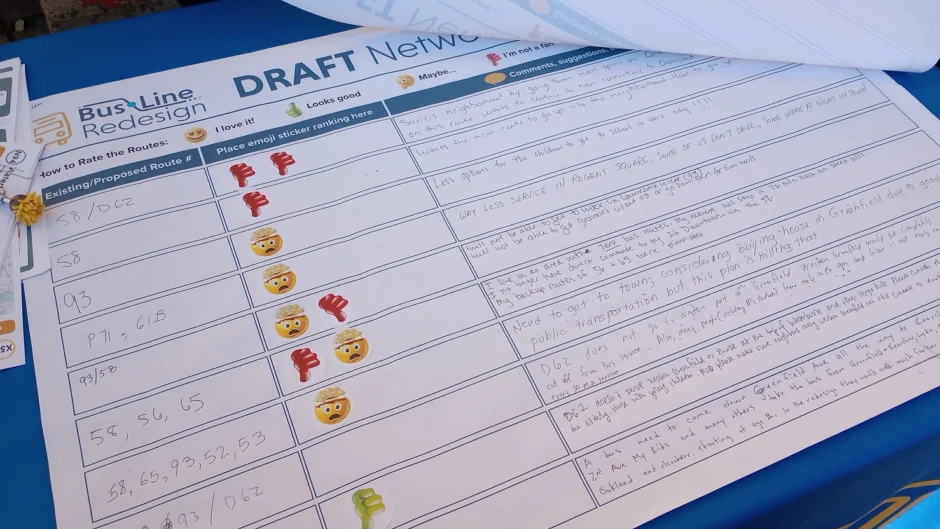

Gabby Gray, lead organizer for Pittsburgh United’s campaign called Our Water Table, worked with other community and advocacy groups on ways to prevent Pittsburgh water from being privatized now and in the future. They drafted this proposed rule and got it on the ballot as a referendum.

In January, the ballot question was introduced and co-sponsored by Pittsburgh City Councilors Deb Gross, R. Daniel Lavelle, Khari Mosley, Erika Strassburger, Barbara Warwick, and Bobby Wilson.

Councilor Theresa Kail-Smith was unconvinced that the measure is necessary, according to a Feb. 4 Trib Total Media article, which quoted her as observing that private companies already supply water in some parts of Pittsburgh. And customers already complain about unaffordable prices.

“I’m just not sure whether the privatization of the utility company is such a bad thing,” she said. “It makes it a little more competitive.”

Even so, City Council on Feb. 3 voted unanimously in favor of the referendum. Mayor Ed Gainey, an early supporter, signed it.

Ms. Gray said during a March 13 interview that Pittsburgh Water will still be accountable to the public once ownership of the water system moves to them. But “accountability and transparency would vanish” if they sold to a private company. She added that Act 12 is part of the reason Pittsburgh’s water needs protection against falling into investors’ hands.

“It is under Act 12 that consolidation, not competition, becomes the issue,” Ms. Gray said. “Under Act 12 utility companies have the space to monopolize the water and sewage systems in Pennsylvania.”

The Our Water Table campaign follows in the footsteps of Baltimore’s charter amendment that made them the first large U.S. city to ban privatization of water.

Fair Shake Environmental Legal Services was part of the coalition that drafted the proposed rule. Brooke Christy, a lawyer with Fair Shake, wrote in a March 14 text, “I’m grateful for the chance to support this community-driven ballot referendum, especially at a time when public services and environmental justice are under attack.”

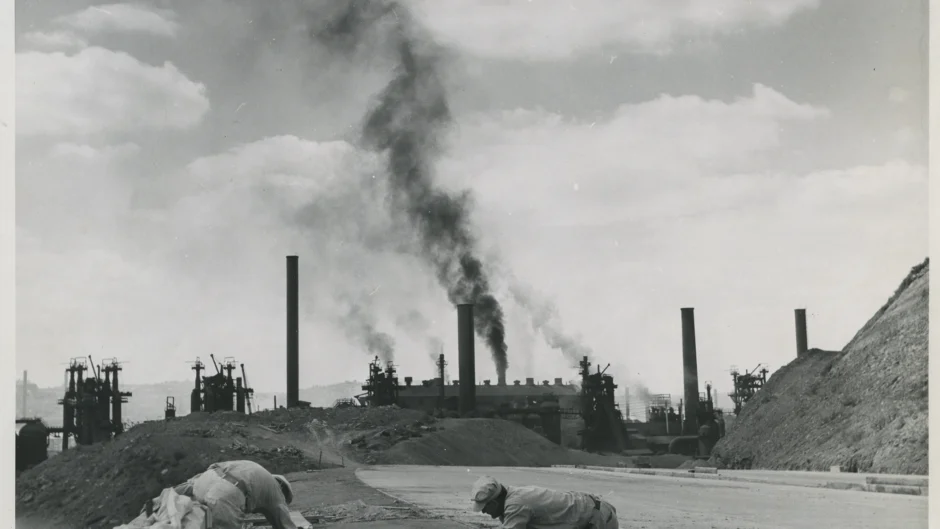

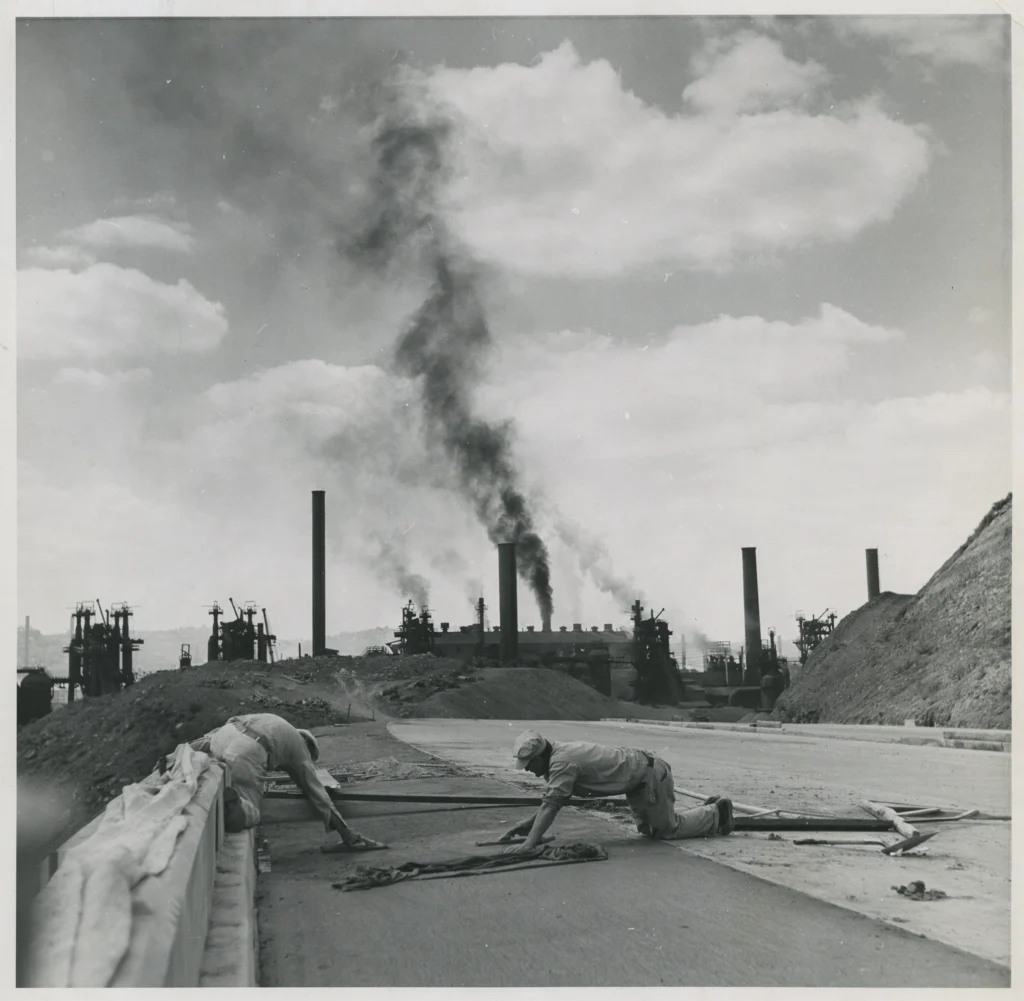

The perils of water for profit

Higher costs and lower service quality plague communities nationwide after they lose control of their water systems. Corporations answer to their stockholders, not those who use their services. This creates an incentive to put profit first.

A 2022 study by Cornell University and University of Pittsburgh researchers found that “[p]rivate ownership is the biggest factor in driving higher water bills.” Nonprofit Food & Water Watch gathered and compared water rates of the 500 largest U.S. community water systems. In their report (last updated in 2021), they found that “investor-owned utilities typically charge 59% more for water service than local government utilities.”

And Pittsburgh has already had a taste of private companies degrading the water supply. In 2012, PWSA hired Veolia Water North America to repair the city’s water system. Veolia changed the chemical control plan to save money, and that ended up leading to lead levels in the water rising even more quickly than before. Pittsburgh later sued Veolia.

Veolia was also involved with the 11-year-old water crisis in Flint, Michigan. Michigan’s attorney general filed a civil lawsuit against Veolia for its role. In February, Veolia reached a $53 million settlement with the state and about 26,000 residents. A year earlier, Veolia settled a separate class action lawsuit brought against it by Flint residents for $25 million.

Ms. Christy said the Pittsburgh initiative “demonstrates the power communities have to create change. By uniting to pass this referendum in May, we can protect our water systems from privatization.”

This article originally appeared in The Homepage.

Recent Comments