Pittsburgh City Controller Michael Lamb’s office released its performance audit of the city’s Department of Mobility and Infrastructure (DOMI) on August 4. The 70-page document examines DOMI’s creation and functions, along with the department’s handling of projects identified as central to its mission.

In the executive summary section of the introductory letter signed by Controller Lamb, he notes that auditors could not assess DOMI’s progress toward some goals “due to DOMI and the previous mayoral administration being unable to furnish records” of DOMI’s early activities. But the audit has useful information for Pittsburghers. Of special interest to District 5 residents are the audit’s findings on traffic calming, distribution of resources, and the Mon-Oakland Connector (MOC).

Traffic calming works, but is applied unevenly

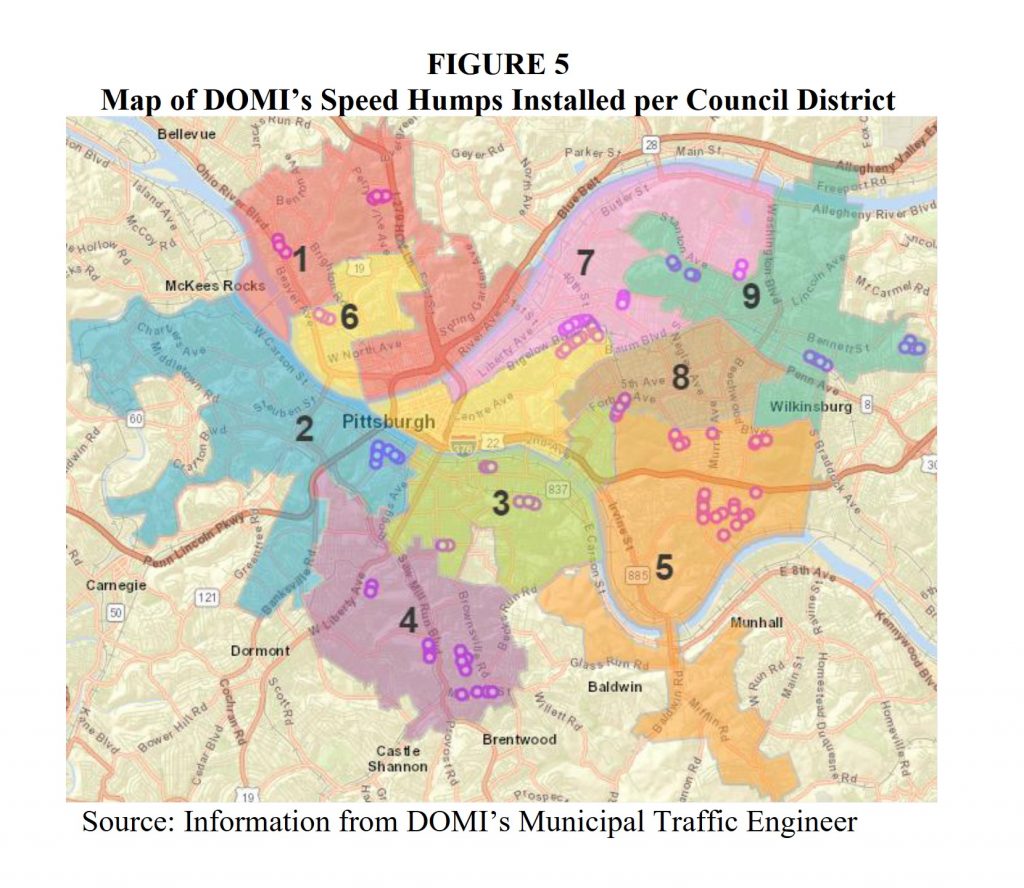

In areas where DOMI has installed speed humps and other traffic-calming measures, the number of drivers exceeding the speed limit has been reduced on average by 38 percent. The audit includes maps of where traffic calming has been put in place and where it is still absent. Figure 5 on page 31 shows a distribution map of speed humps across Pittsburgh’s nine council districts. Markers show speed humps in District 5 concentrated at the northern end, in Squirrel Hill South.

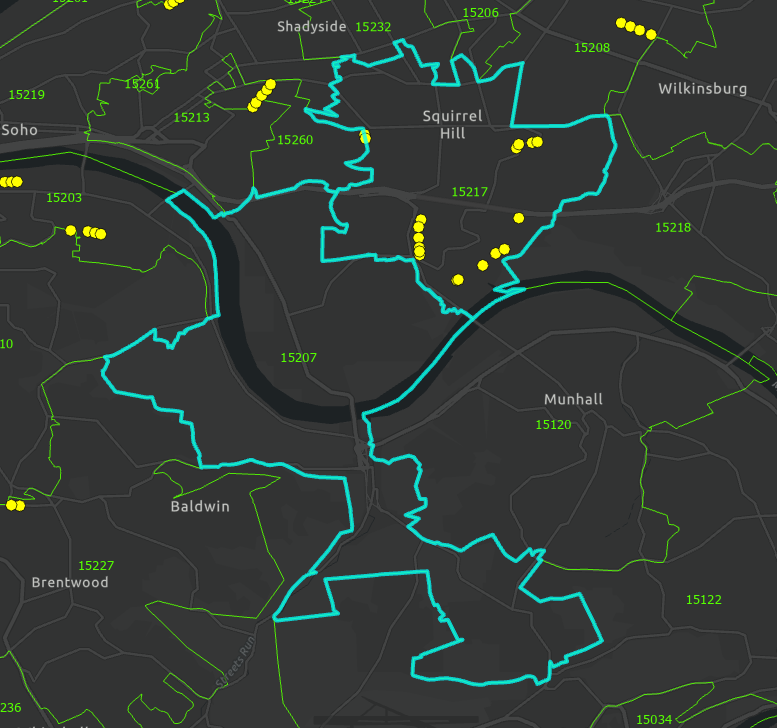

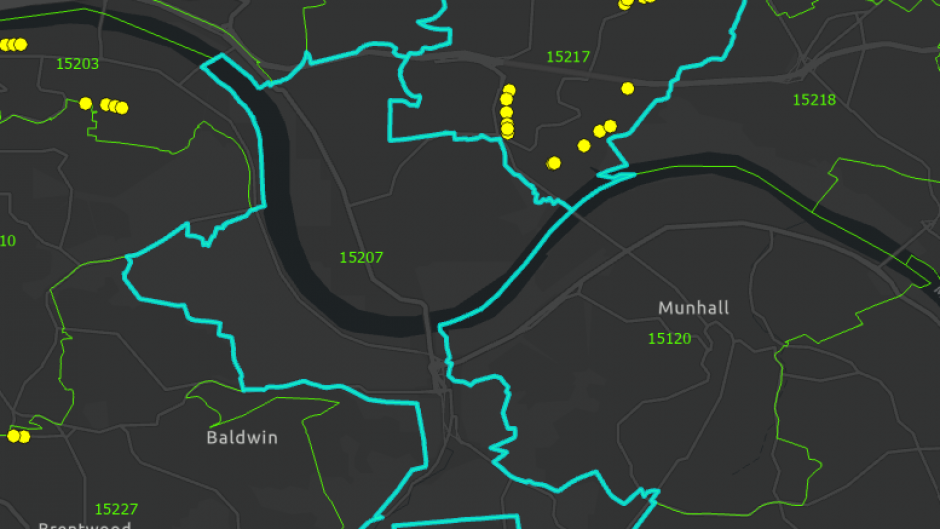

District 5’s two ZIP codes highlight the disparity. A closer look using the Western Pennsylvania Regional Data Center website shows that none of District 5’s 21 speed humps (18 shown, 3 so new they have not yet appeared in the system) are in 15207 (Greenfield, Greater Hazelwood, and the 31st Ward), although dangerous roads in these neighborhoods require urgent attention.

Street selection for repaving should be data-driven

Wealthier neighborhoods also enjoy better street maintenance, possibly for similar reasons. Before 2018, resources for streets in the worst condition (scored on an index) were split into Department of Public Works (DPW) divisions. DOMI’s director changed the method in 2018 so that money is split evenly among council districts.

According to recommendation 10 of the audit, “Before concrete and accessible data existed, it was arguably a good idea to tie paving projects in with council districts to ensure equity across the city. However, we now have more comprehensive data, and as a result, more data-driven decisions can be made.”

The audit’s findings call for a return to dividing this work into DPW districts. This would encourage paving streets in worse repair first instead of “dividing the budget by political boundaries,” as stated on page 41. They also suggest avoiding an over-reliance on calls to the city’s 311 system for input, which leads to a “squeaky wheel” approach that can elevate neighborhoods with many 311 callers above those most in need.

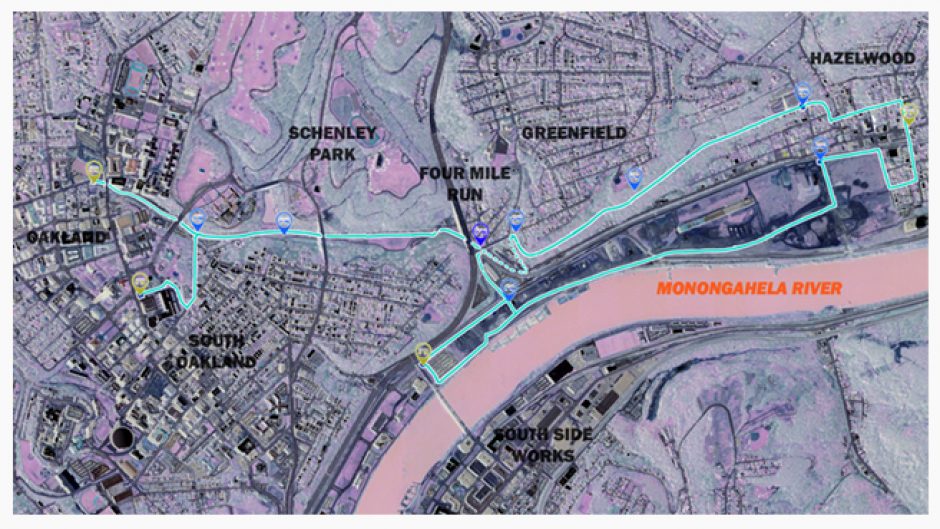

The MOC has deeper problems than its name

Although the audit points out DOMI’s lack of transparency, its discussion of the MOC relies on DOMI’s characterization of the project. As a result, the audit contains several inaccuracies about the MOC.

On page 24 it states, “The [MOC] project would also address flooding and stormwater issues and include the implementation of green infrastructure.” However, the MOC has always been a separate project from the Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority’s (PWSA’s) Four Mile Run Stormwater Project. PWSA originally planned to work on their project in the same physical location as the proposed MOC; that is why PWSA submitted a joint application for both projects during the permitting process. But PWSA’s project received no funding until nearly two years after the MOC was announced. In fact, the original grant for the MOC sought by the city and its partners in 2015 stated in its guidelines that funding could only be used for the shuttle road—not to fix flooding in the area.

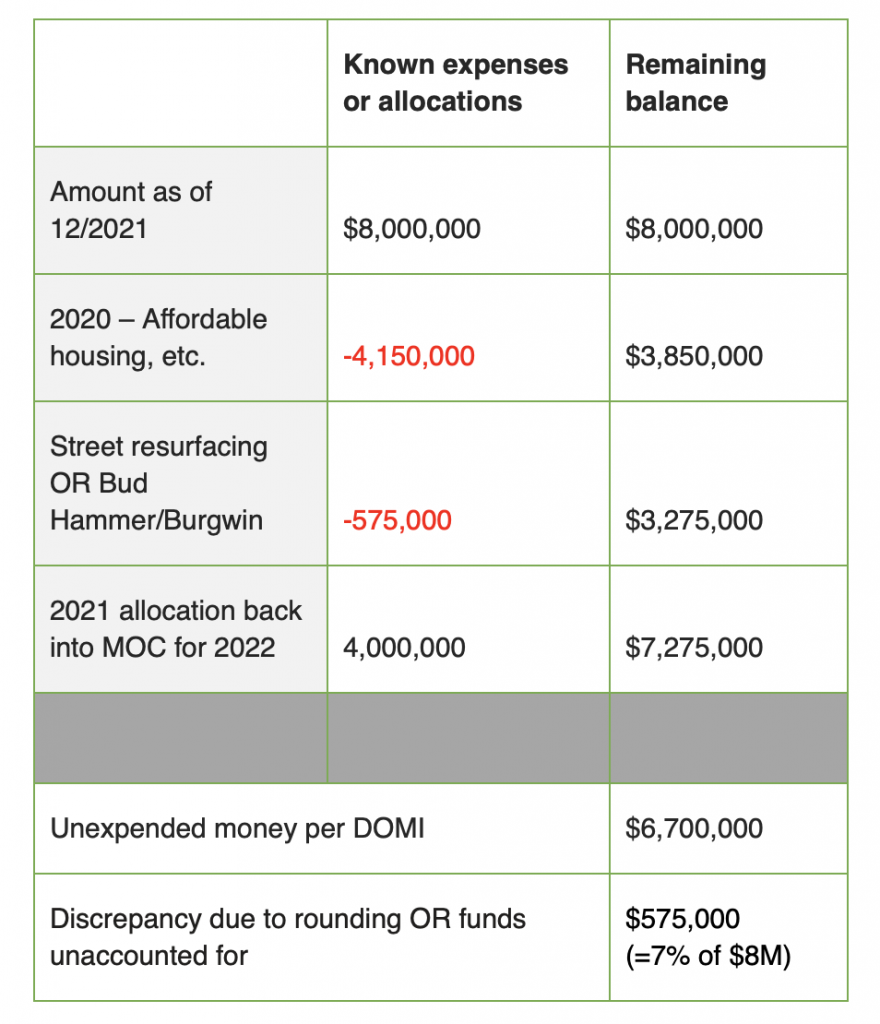

The audit continues, “The consensus from the second public meeting found citizens selected electric scooters, electric bike-share systems, and electric shuttles to be the ideal solutions.” This statement is not sourced, but seems to have come directly from DOMI. As the audit later notes, the MOC lacked community support from the beginning—partly because the project’s estimated $23 million budget should instead go to infrastructure needs outlined in the community-generated Our Money, Our Solutions plan. These include traffic-calming interventions.

Controller Lamb’s office makes no recommendations concerning the MOC project and their only finding is as follows: “The auditors found that multiple names for this shuttle program were used to reference it. This causes confusion to the public. For example, Mon-Oakland Shuttle, Mon-Oakland Connector Shuttle or just Mon-Oakland Connector were found to be used interchangeably.”

Even so, Controller Lamb stated in a May 27 email that the audit’s review of the MOC helped inform Mayor Gainey’s decision to end the unpopular project.

Recent Comments