After Charles Anderson Memorial Bridge abruptly closed in February, Pittsburghers welcomed Mayor Ed Gainey’s announcement that the city will complete a full rehabilitation—even though it means the bridge will remain closed for a few years instead of the four months originally projected for temporary repairs.

Emily Bourne, a press officer in Mayor Gainey’s office, wrote in an April 13 email, “Charles Anderson design is tentatively set to finish in Fall 2023 with construction anticipated to begin in Spring 2024. Ideally the bridge would reopen to traffic by late 2025.”

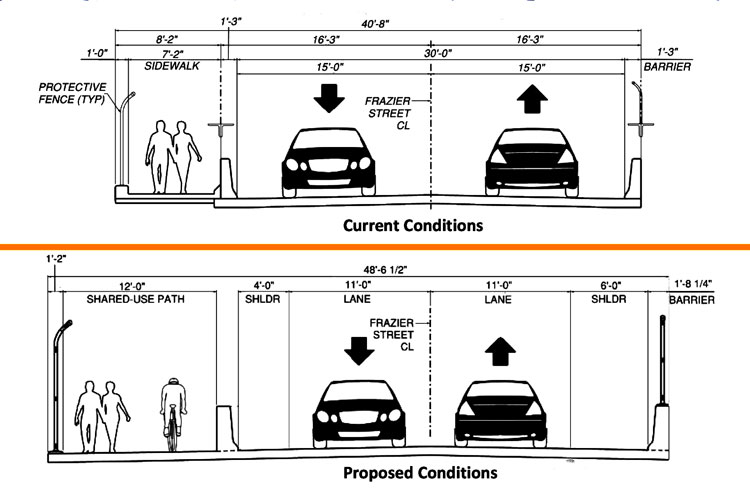

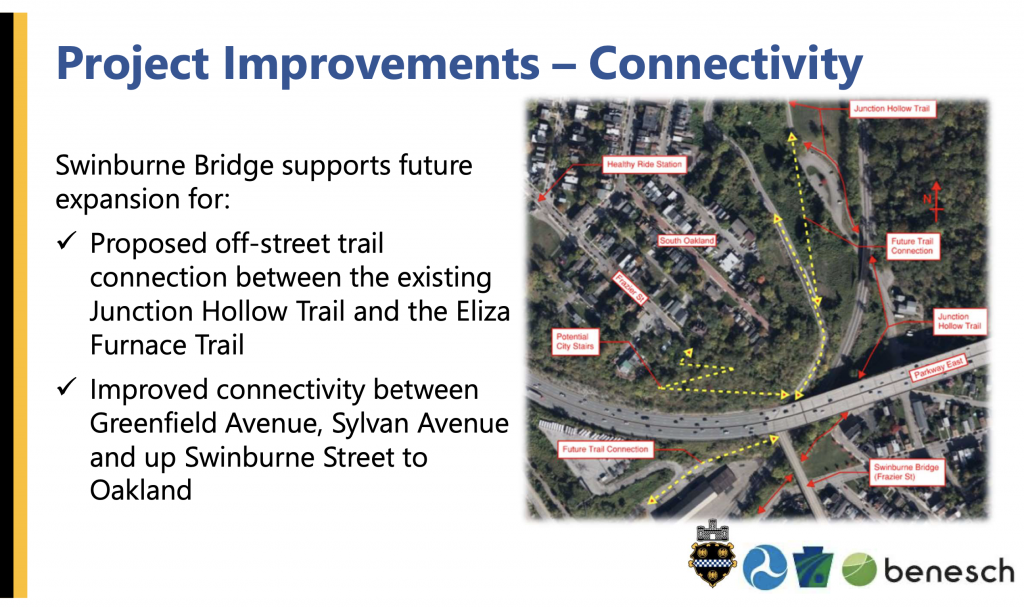

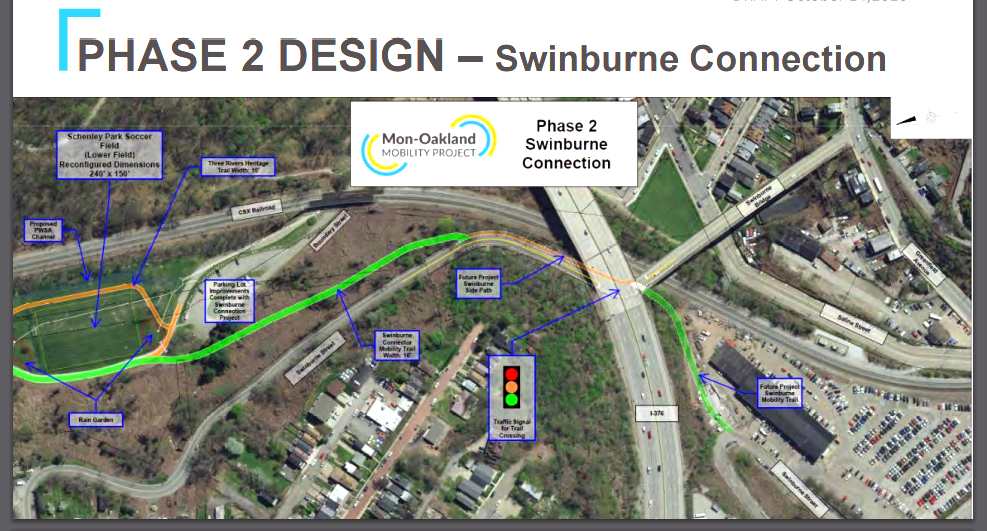

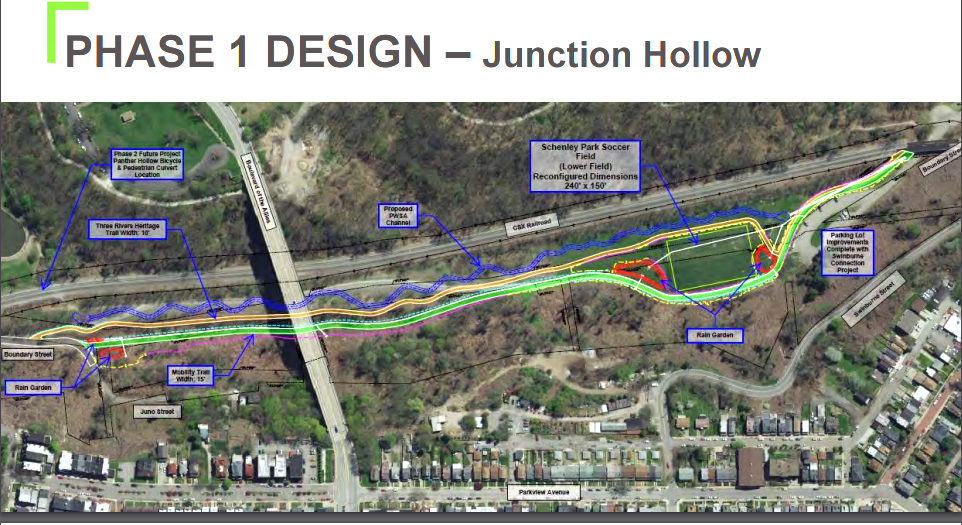

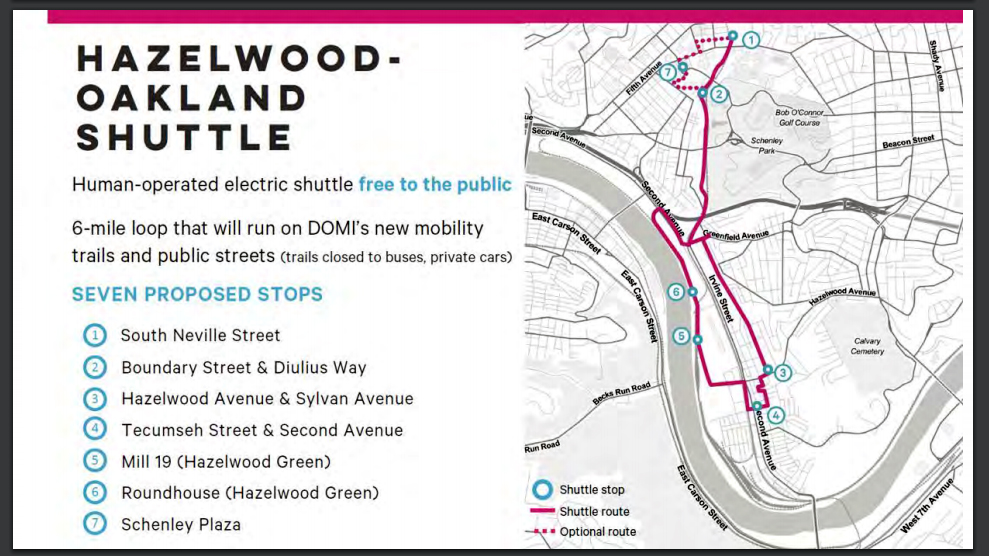

Residents of The Run who live around nearby Swinburne Bridge, also scheduled for replacement, have questions about what the new plan means for them. Until the city closed Anderson Bridge, Swinburne Bridge had been on track to be replaced first. The Run was threatened with erasure by the Mon-Oakland Connector (MOC) shuttle road, which Mayor Gainey halted in February 2022. The planned MOC route included a rebuilt Swinburne Bridge with a dedicated shuttle lane.

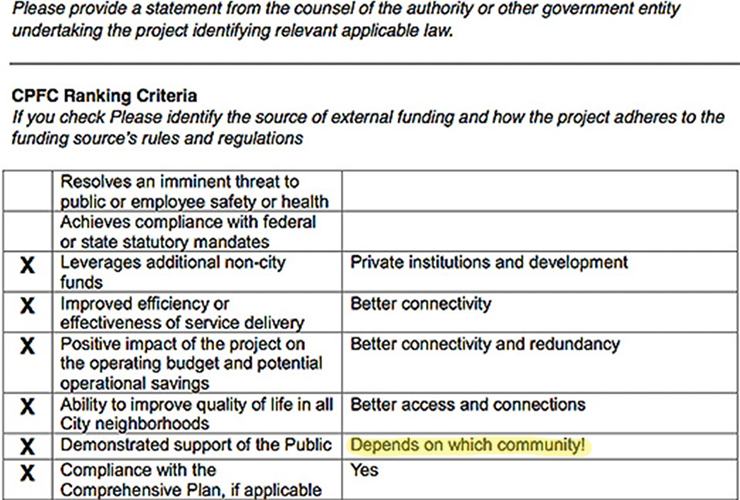

As the Swinburne Bridge project moves forward without the MOC, Pittsburgh’s Department of Mobility and Infrastructure (DOMI) has continued its odious track record of prioritizing high-powered profiteers above communities. But the Anderson Bridge closure gives DOMI an opportunity to change course. They should reset the Swinburne Bridge project to include public decision-making—even if that means a short delay.

A tale of three bridges and one dangerous street

The first public meeting about rehabilitating Anderson Bridge hasn’t been scheduled yet, but DOMI has already posted a presentation about it on the project’s Engage Pittsburgh webpage. After the Fern Hollow Bridge collapsed in early 2022, Pittsburgh officials told the public to expect limited involvement in the rebuild because of its urgent nature. Even so, artists and residents had time to discuss ways to honor the span’s history and connection to Frick Park.

By contrast, DOMI ignored repeated requests for DOMI’s presentation on plans for Swinburne Bridge until about four hours before the first of only two public meetings on the project. Then project manager Zachary Workman posted a statement denying the requests. DOMI’s community outreach consisted of a letter sent to a few residents who live near the bridge, which they received 10 days before the original meeting date.

At the July 2022 meeting, representatives from DOMI, PennDOT, and private construction firm Alfred Benesch & Company all acknowledged that work on Swinburne Bridge will profoundly affect The Run. A significant portion of the neighborhood—and the only street providing vehicular access to it—lies directly beneath the bridge.

DOMI painted a rosy picture of plans to minimize disruptions to the community, but avoided promising that residents would not have their homes taken through eminent domain. They also avoided any commitment to calm dangerous traffic along Greenfield Avenue.

DOMI ruled out even adding a traffic signal at the intersection of Swinburne Bridge and Greenfield Avenue until after construction on Swinburne Bridge wraps up in 2026 (at the earliest). Residents have been advocating traffic-calming measures along the nearby 300 block of Greenfield Avenue for more than eight years. They face speeding traffic every time they walk between their houses and cars. Several accidents, including some that totaled parked vehicles, occurred there in 2022 alone.

Moving traffic without mowing down residents

Affected residents, commuters, and DOMI all agree that closing Anderson and Swinburne bridges at the same time would cause far-reaching traffic nightmares.

According to Ms. Bourne, “Based on the traffic observed with Charles Anderson being closed, it is apparent that construction cannot begin on the Swinburne replacement project until Charles Anderson has reopened to traffic.”

While Anderson Bridge remains closed, the posted detour includes Greenfield Avenue.

Bumper-to-bumper traffic now provides a brief respite from leadfooted drivers during rush hour, but the rest of the time, they continue to speed.

Whose needs is DOMI serving?

There is no getting around the fact of competing priorities for Greenfield and Hazelwood. Residents need safer streets, while investors in the Hazelwood Green development have long desired a “permanent, rapid link” that moves traffic as quickly as possible between their site and Oakland university campuses. This explains DOMI’s continued prioritizing of MOC-related projects above community needs even after the MOC’s demise.

Taxpayer-funded institutions should be working against such an extreme power imbalance instead of deepening it. We are calling for DOMI to:

- Prioritize the physical safety of existing residents by adopting the Our Money, Our Solutions plan. Residents from MOC-affected neighborhoods created the plan in 2019 to point out infrastructure improvements Pittsburgh should be funding instead of the MOC. Several items in the plan have since been addressed—but not traffic calming on Greenfield Avenue.

- Follow the public engagement guidelines/demands posted at junctioncoalition.org/2022/07/26/pittsburgh-community-engagement-needs-more-of-both/. These are commonsense provisions like notifying the public of meetings and sharing presentations at least 14 days in advance so that people can come prepared with relevant questions. City officials are aware of these guidelines but have not responded.

- Reboot the Swinburne Bridge Project, starting with additional public meetings. The next public meeting is not scheduled to be held until the “final design” phase of the project. Plans established before the first meeting call for a rushed, cookie-cutter design that skipped public input. With work on Anderson Bridge expected to last at least through 2025, there is plenty of time to reassess this approach—and no excuse not to.

Recent Comments