On April 26, Pittsburgh’s Department of Mobility and Infrastructure (DOMI) hosted a meeting via Microsoft Teams to kick off public engagement on its Sylvan Avenue Multimodal project, presenting early plans and fielding questions from community members.

Many of those questions revealed concerns about the project’s limited scope, its priority level and timing, and its potential effects on residents along Sylvan Avenue.

A project within a project

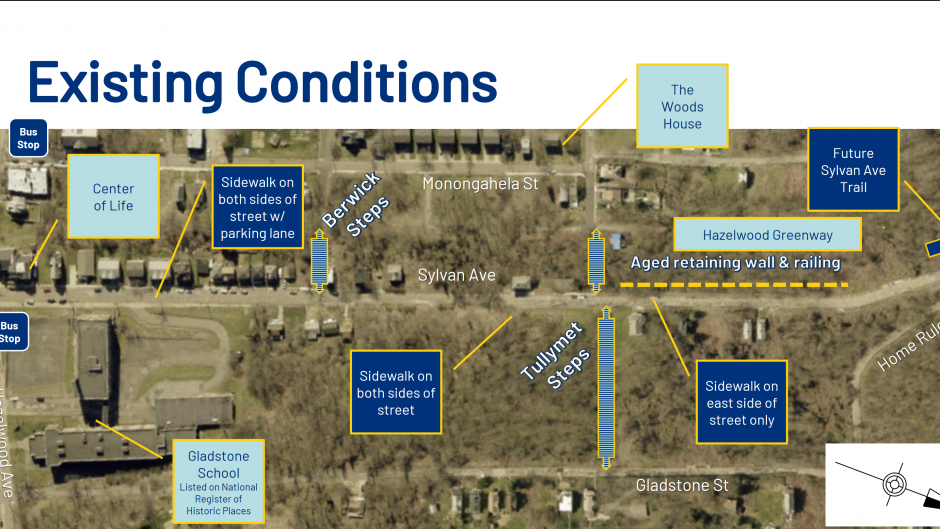

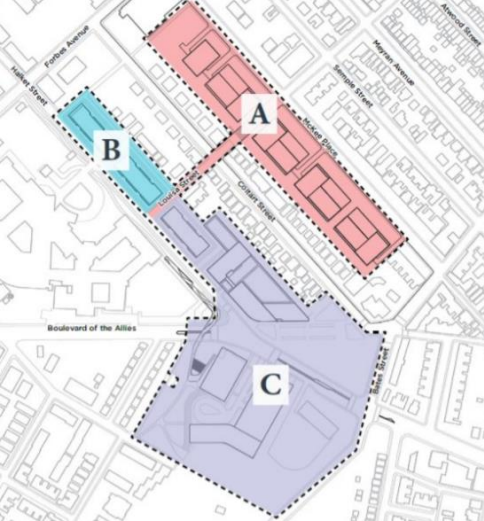

The Sylvan Avenue Multimodal project is one part of a pedestrian/cyclist trail that replaces—but follows the route of—the controversial Mon-Oakland Connector (MOC) shuttle road between Greenfield and Hazelwood avenues. The stretch of Sylvan Avenue between Home Rule Street and Greenfield Avenue (currently closed to traffic) is also part of the trail but considered a separate project.

According to DOMI project manager Michael Panzitta, the City of Pittsburgh received a $1.76 million state grant to restore the closed part of Sylvan Avenue for bikes and pedestrians only. Along with separate funding, work on the Home Rule-to-Greenfield stretch of Sylvan Avenue will come with its own set of public meetings.

Discussion at the April 26 meeting was limited to plans for Sylvan Avenue between Home Rule Street and Hazelwood Avenue.

That work includes reconstructing the sidewalks, repaving the street, and adding features to slow down traffic. Two of the biggest traffic-calming features are raised pedestrian crosswalks at two sets of city steps, and landscaping near the entrance to the trail.

In addition, Sylvan Avenue is set to be designated as a Neighborway street, meaning it is a low-traffic street designed for the needs of people on foot, bikes, or other nonmotorized vehicles.

A combination of city and federal funding

The City of Pittsburgh is funding the design phase and street repaving. Construction funding comes from a federal grant with Pennsylvania Department of Transportation oversight, explained Leon Jeziorski of Michael Baker International, the multimodal design firm for the project.

Mr. Panzitta was unclear on the source of federal funding. In a May 9 email, he referred funding questions to Emily Bourne, DOMI communications specialist. Ms. Bourne replied to emailed inquiries that she was coordinating her response with that of Mayor Gainey’s press secretary, Maria Montaño, who had been contacted separately.

Community concerns include parking, safety

During the Q&A portion of the meeting, residents raised concerns about pedestrian safety on Hazelwood Avenue and the limited parking available on Sylvan Avenue.

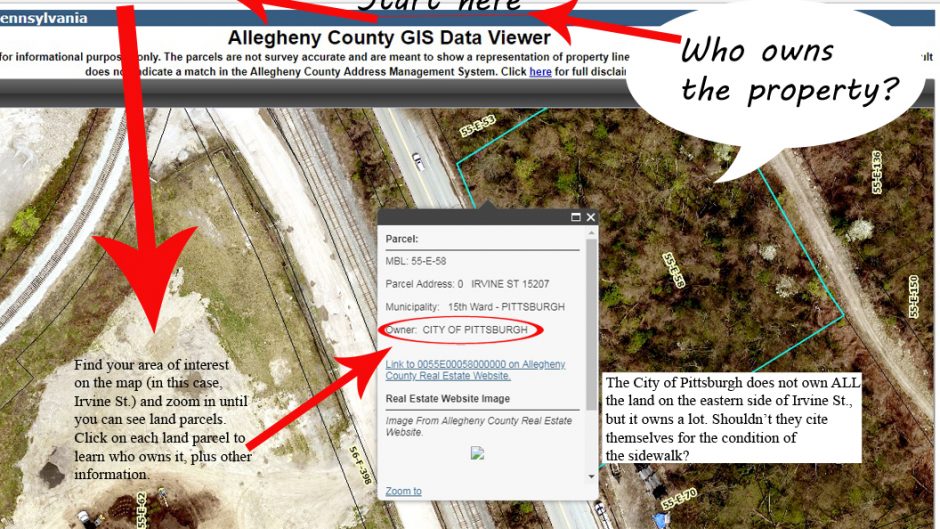

Pastor Tim Smith, CEO of Center of Life—located at the intersection of Hazelwood and Sylvan avenues—asked if the project will widen the road. He said people park on both sides at that end of the street, which leaves a narrow space for drivers passing in opposite directions. Mr. Jeziorski responded that the project would not address parking issues, and the east side of the street (across from the Center of Life) is currently a “no parking” zone.

A Sylvan Avenue resident who did not give her name said enforcing the “no parking” zone would prevent residents from parking near their homes.

Roy Simms, who said he’d lived on Sylvan Avenue for more than 50 years, asked if the city steps would be repaired as part of the project. Mr. Panzitta answered that the steps are also outside the project’s scope.

Why here, why now?

Several attendees wanted to know more about why this project was identified as a priority now. Despite being touted as a safe multimodal connection, it does not address issues with the steps, the decrepit retaining wall and railing near the future trail entrance (the project will use landscaping to block off the railing rather than fix it, according to Mr. Jeziorski), or dangerous conditions at either end of Sylvan Avenue.

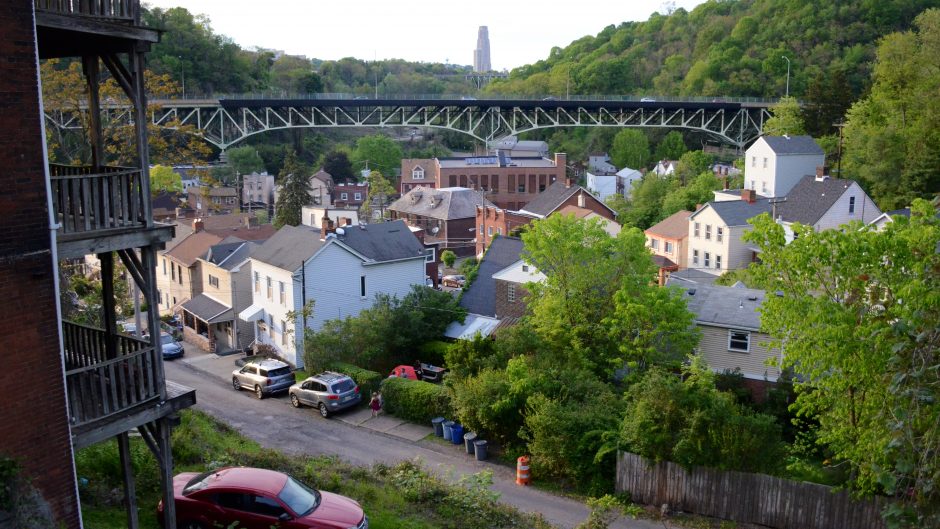

“If you’re looking to increase bike accessibility in a safe way, there’s a lot of already-existing safety issues with Greenfield Avenue,” said Eric Russell, a Greenfield resident and daily bike commuter. “Especially if you’re dumping people onto Greenfield Avenue from Hazelwood.”

Catherine Adams lives on Hazelwood Avenue and said some of her neighbors have been hit by cars. They have been meeting with DOMI and District 5 Councilman Corey O’Connor about speeding and safety issues on Hazelwood Avenue for the past two years.

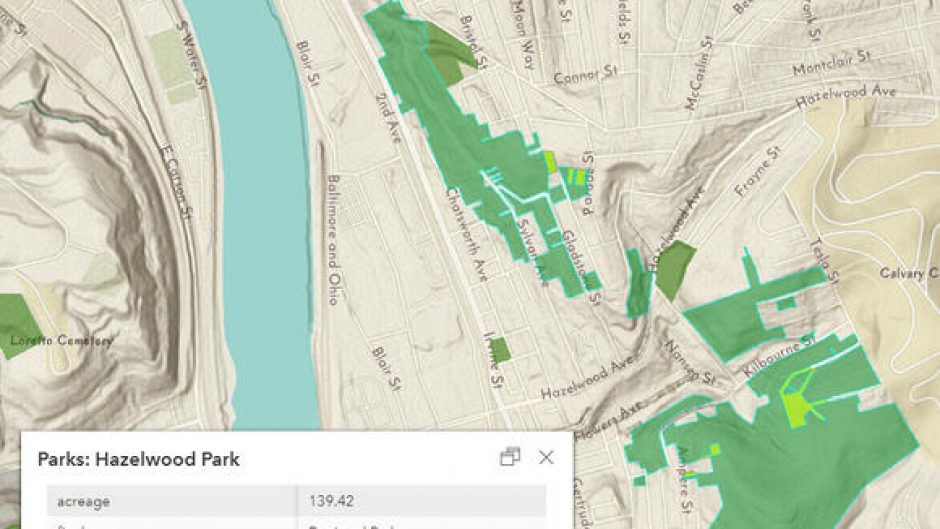

Mr. Panzitta said the trail is included in the Greater Hazelwood Neighborhood Plan. Page 96 lists “creat[ing] a bicycle route up the hill from and parallel to Second Avenue” as a way to “address gaps in multi-modal network throughout the neighborhood.”

Mr. Jeziorski defended the project, asserting that improved accessibility to this corridor will draw more residents and businesses to the neighborhood. The increased activity should help Hazelwood get grant funding to replace the steps. “So this is a building block that can help with other improvements in the future,” he said.

Recent Comments